IFC on Fostering Financial Inclusion via Fintech Investments in Africa

25 May 2023•

IFC, or the International Finance Corporation, is a member of the World Bank Group that focuses on promoting private sector development in emerging and developing markets. IFC provides financing, advisory services, and technical assistance to businesses in emerging markets, to help them grow and create jobs, with a particular focus on supporting sustainable and inclusive growth.

Over the past 25 years, IFC has invested more than US $67 Billion into African businesses and financial institutions, and IFC’s current portfolio exceeds US $13 Billion. IFC has also been playing a critical role in developing the fintech ecosystem in Africa, with the aim of promoting financial inclusion on the continent. IFC began investing in fintech in Africa in 2008, when the institution funded South Africa’s Wizzit – the first mobile wallet provider that was independent of a telecommunications player, that focused on the underserved and unbanked population.

Today, IFC’s fintech portfolio in Africa spans investments in over 60 companies, spanning a range of sub-sectors such as digital payments, digital lending, capital markets and insurance. IFC believes fintech can play a major role in achieving financial inclusion, because fintech has the potential to lower costs, while increasing speed and accessibility, allowing for more tailored financial services that can scale.

I sit down to speak with Kareem Abdel Aziz, the Global Lead of Digital Payments investments at IFC to speak about his take on Fintech in Africa, and where the world is at on the journey towards financial inclusion. Kareem provides some context on the role that IFC plays in the African fintech ecosystem. “Though we have a sustainable development and a sustainable impact mission,” he says, “we remain very commercially-minded. It is our belief that investments which make a sound financial return, are also helping to drive sustainable economic growth in the wider economy.” “Today, we generally try and make later-stage, Series B+ direct investments, and are also supportive of early-stage growth by investing in earlystage funds, like Algebra Ventures and Disruptech Ventures in Egypt and pan African funds like Partech.”

“How we differ from traditional VCs and institutional banks, is that our capital can be a bit more patient.” As a balance sheet investor, with no liquidation requirements, Kareem tells me that he finds that IFCs capital injections into startups allow founders a bit more breathing room to set-up the robust operational foundations needed before scaling aggressively. “We also have a mandate to help develop and capitalize under-served markets and sectors, which means we are often the first major global investors in frontier markets.” To that effect, IFC launched a $225 million platform last year to strengthen venture capital ecosystems in Africa, Middle East, Central Asia, and Pakistan, and invest in early-stage companies there. In 2021, these regions collectively received less than 2% of $643 billion of global venture capital funding. In addition, IFC has funded the likes of mobile payments player Wave, as well as digital payment platform, Fawry in Egypt. IFC is often the only international investor on African startups’ cap tables when they first invest, and takes pride in shepherding in other institutional and strategic investors into future funding rounds.

“Most global investors understandably come-in a bit blind to the macroeconomic, regulatory and implementation risks to deals in Africa, and that’s where I think IFC can be a great partner.” Kareem explains that IFC does all of that upfront assessment and due diligence on the ground, including thorough IDD checks on all the founders they back. “Startups we back are strongly vetted, because we are making higher-risk bets in frontier markets that inherently have more risk baked into them.”

Not only does it sound like IFC brings a big rubber stamp of approval onto the fintechs they back, but with it, access to and introductions to strategic international investors. Having a presence in over 100 countries worldwide, IFC also brings with it the resources of the World Bank and its research and development arms, that can help their startups make headway towards regional and global expansions. “I think something else that makes IFC unique as an investor, is our ability to provide access to a broad range of investment products to our startups,from equity investments all the way up to debt-financing,” says Kareem. “IFC has the ability to work with local banks and help structure these deals, where local players may not have ever executed such deals in the past.”

Fintech Investments for Financial Inclusion

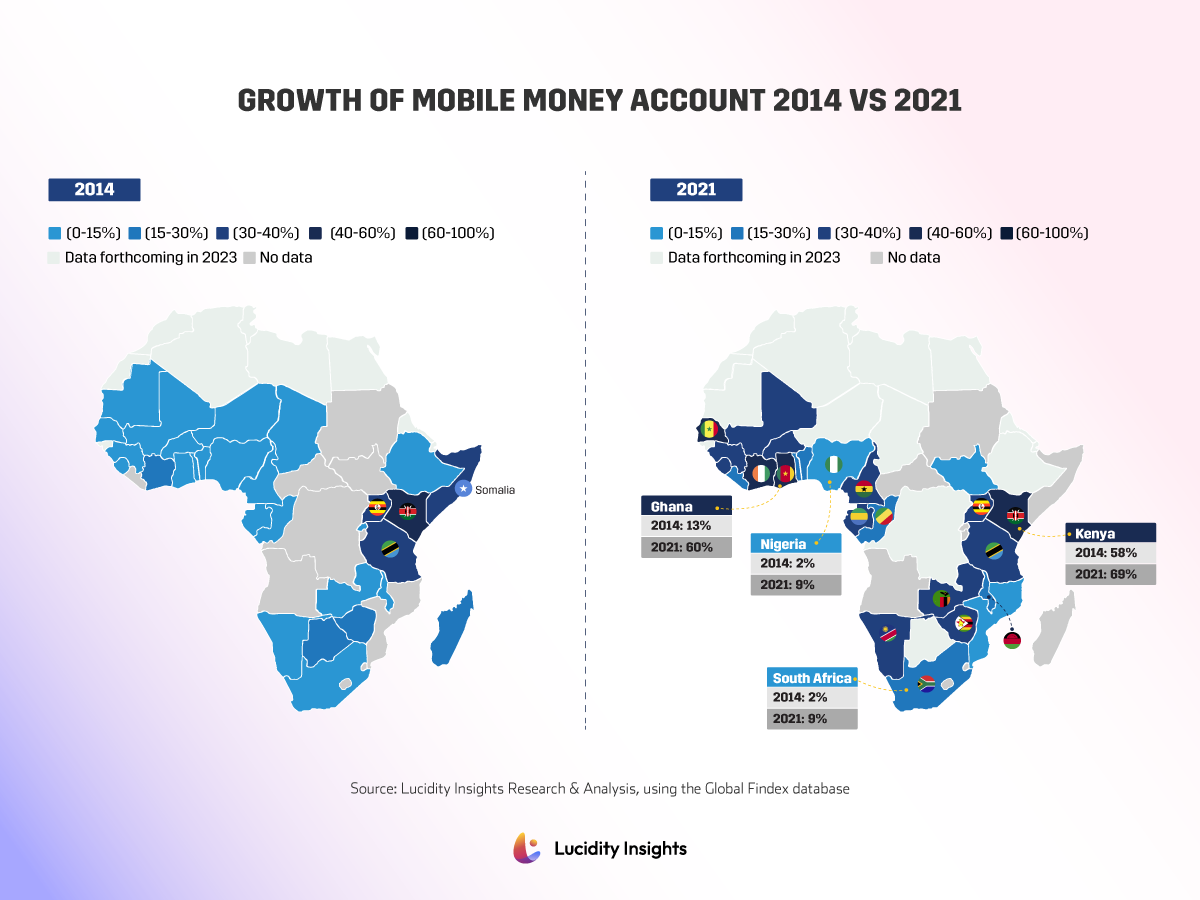

According to the World Bank, over the past decade from 2011-2020, 1.2 billion previously unbanked adults gained access to financial services for the first time, and the global unbanked population fell by 35%; this was primarily boosted by the increase in mobile money accounts. While more than 1.7 billion adults, equivalent to 22% of the world population, remain unbanked globally, fintech is helping make financial services more accessible to an increasing number of people.

Infographic: Growth of Mobile Money Account in Africa (2014 vs 2021)

In recent years, IFC has been investing in various fintech startups, as well as infrastructure players in telecommunications and banking. IFC provides them with the necessary support to grow their businesses and expand their reach, with the ultimate aim of promoting financial inclusion. Here are just some recent examples of IFC investments in Africa, to paint a picture of the breadth of their involvement:

1. Investing in Infrastructure to Achieve Accessible Internet for All.

In 2020, IFC announced an $100 million investment in Liquid Telecom, a leading pan-African telecommunications company that provides independent data, voice and IP solutions to eastern, central and southern Africa. The investment was aimed at supporting Liquid Telecom’s efforts to expand access to affordable and reliable internet and cloud services across the continent, particularly in underserved and rural areas.

2. Investing in Financial Institutions Supporting SME Financing.

In 2019, IFC invested $200 million in the Commercial International Bank (CIB), one of Egypt’s largest private sector banks. The investment was part of a broader effort by IFC to support Egypt’s financial sector and promote inclusive growth in the country. IFC’s investment in CIB was earmarked to help the bank expand its lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and support the growth of Egypt’s private sector. SME financing is important, as the World Bank estimates that SMEs account for 90% of businesses patronized by the African population, and seven out of 10 jobs are created by SMEs on the continent.

3. Fintech Investments.

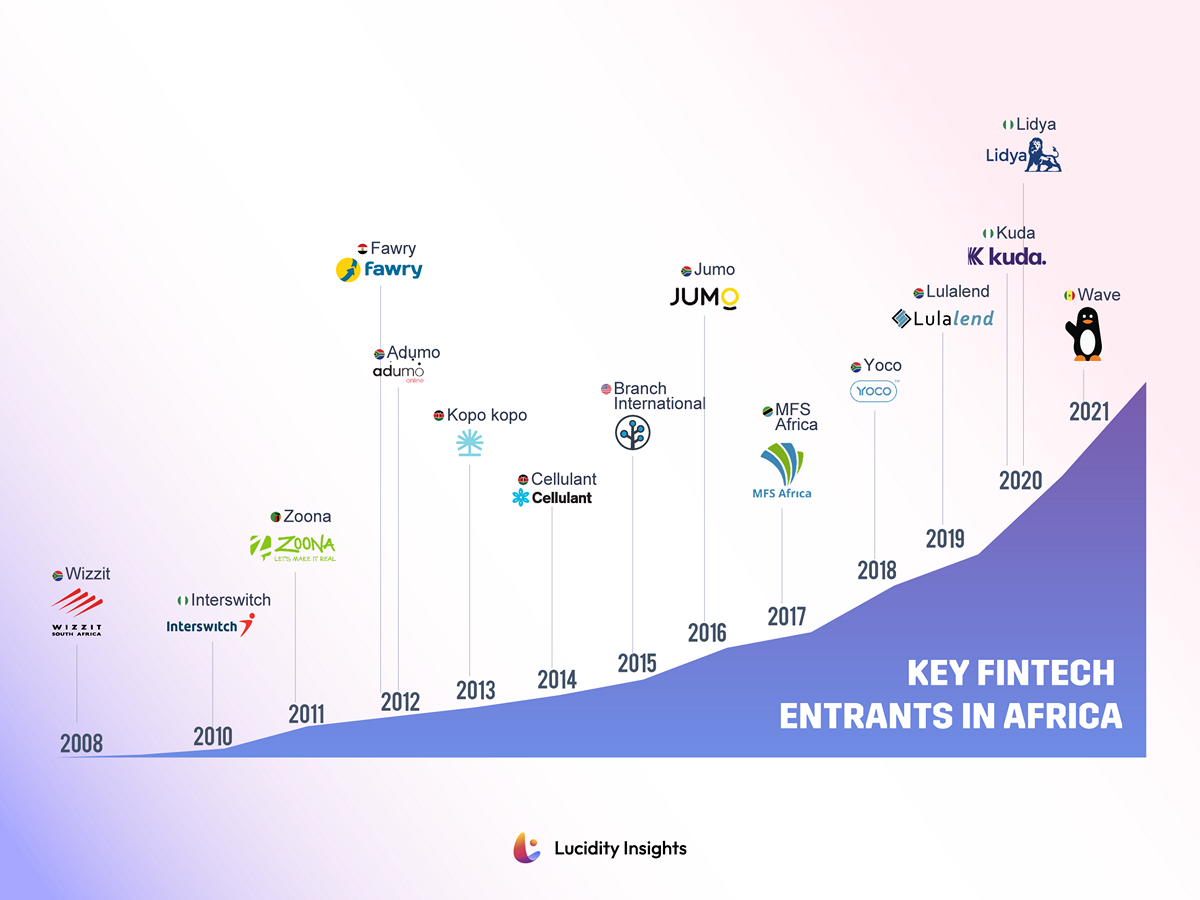

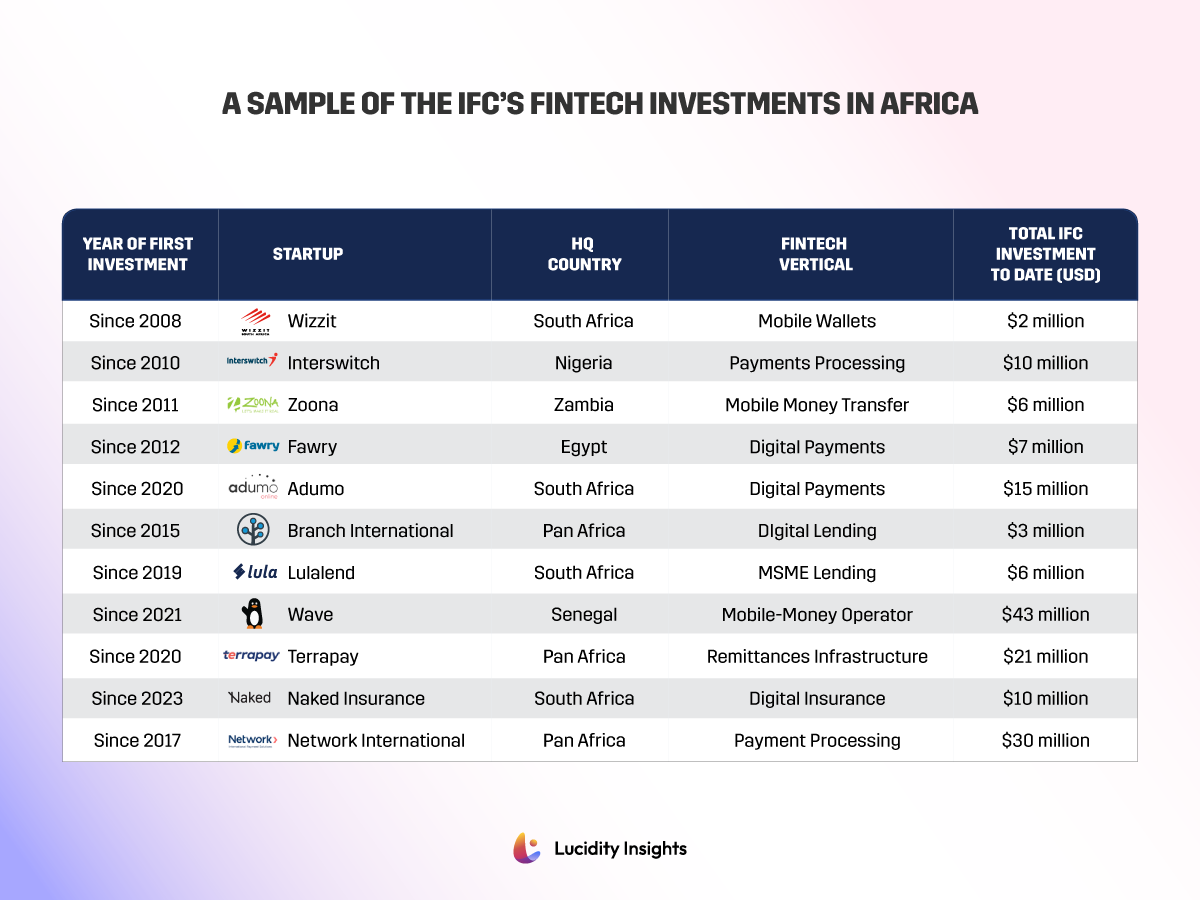

IFC has been a key investor in Africa’s fintech space, having invested in many of the most prominent fintech startups the continent has produced thus far, including but not limited to the following:

Infographic: IFC’s Key Fintech Entrants in Africa

Table: A Sample of the IFC’s Fintech Investments in Africa

The fintech sector in Africa has been growing rapidly, with innovative solutions being developed to address the financial inclusion gap on the continent. According to a report by Disrupt Africa, there were over 400 fintech startups in Africa as of 2020, with total funding of over $1.3 billion. As of 2022, Lucidity Insights research has identified over 270 fintech “scaleups”, which are defined as startups that have each raised a minimum of US $1 million. IFC has been at the forefront of fintech in this region, providing funding and support to some of the most promising fintech startups in Africa.

IFC is also working with fintech startups to develop solutions that address the unique challenges of the African market. For example, IFC is supporting startups that are developing solutions for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Africa, which often struggle to access financing through traditional channels. IFC is also supporting startups that are developing solutions for the informal sector, which comprises a significant portion of the African workforce.

In addition to its work with startups, IFC is also supporting the development of the fintech ecosystem in Africa through its partnerships with financial institutions and regulators. IFC is working with banks and other financial institutions to develop digital banking solutions that can reach underserved populations in Africa. They also work with regulators to develop policies and regulations that can support the growth of the fintech sector in Africa, while ensuring that consumer protection and financial stability are maintained. Despite the significant progress that has been made in developing the fintech ecosystem in Africa, there are still many challenges that need to be addressed. One of the main challenges is the lack of infrastructure and access to reliable internet connectivity in many parts of the continent. There is also a lack of trust and awareness of digital financial services among many Africans, and of those that are aware of financial services and want to trust it – many of them lack the necessary documentation such as a national ID card or proof of address to set-up bank accounts.

Despite these challenges, there is significant potential for the fintech sector to drive inclusive growth and financial inclusion in Africa. According to a report by the McKinsey Global Institute, digital finance could add $3.7 trillion to the GDP of emerging economies by 2025, and generate 95 million new jobs worldwide. By continuing to support the development of the fintech ecosystem in Africa, IFC is helping to unlock this potential and create new opportunities for millions of Africans.

The Next Decade of Fintech in Africa

“We are going to increasingly see fintechs that are going to offer a customized solution for customized and niche population segments, like farmers,” says Kareem. Fintechs are inherently more nimble and cost-effective compared to financial institutions which are often hampered by legacy technologies and legacy business models. Therefore, fintechs are still better positioned than institutional banks to reach the unbanked. Kareem adds, “the old paradigm in financial inclusion was banks needed to educate the underserved communities about finance. The new paradigm in financial inclusion will require financial institutions, most likely fintechs, to educate themselves about their target customers and how they can seamless integrate into their lives. It’s these types of customer-obsessed fintechs that are building really interesting startups today that have real stickiness.”

One example provided was Mozara3, an Egyptian fintech solution serving rural farmers. Mozara3 goes out to small plot farmers, evaluates the land and assesses the quality of the produce. They then aggregate all of this produce from multiple farms, and sell wholesale or directly to big retailers. They provide the farmers with working capital financing to buy seed, fertilizer and equipment, and manage the entire sale. “Currently Mozara3 is still in the early stages,” Kareem notes, “so we’re just providing technical support at the moment. But we think this is a very promising startup in the very early days of development.”

Kareem comments on the fintech investments being made over the last decade being defined as financial inclusion focused, and the future being more about systems building and integration. “We’re really in a pivotal point in history, where for the first-time in human history, financial services is morphing from a vertical sector, to becoming an omnipresent horizontally integrated solution that will become an underlying infrastructure across every sector imaginable.”

Kareem continues, “The last decade was defined in bridging the access gap in financial services, the next decade will be defined in integrating financial services into day to day economic transactions.”

As for the current venture capital winter and the impact on fundraising for African fintechs, Kareem stated, “unfortunately, the US still has major influence around the world due to the US dollar being the de-facto reserve currency. So that means that every time the Fed raises interest rates, it strengthens the US dollar, and weakens many emerging market currencies.”

When I ask him what this means for the next 24 months, he says, “it means there may be vulnerabilities in markets like Nigeria, Turkey, Egypt and Pakistan. As VC funds tend to raise capital in US dollars, there will be pressure on VCs to hedge foreign currency risk by going and investing in markets where foreign currency is more stable, or have no choice but lower valuations.”

That said, Kareem reassures that there is a lot of dry capital in many war chests abound. The expectation is that this dry powder will be provided to fund current market leaders, to help them consolidate their market leadership position through acquisitions over the next year or two.

“Downturns are very healthy and welcome,” says Kareem. “They help us flush out the less sustainable business models, startups and investors, which is good for the entire ecosystem as a whole.”

%2Fuploads%2Ffintech-africa%2Fcover13.jpg&w=3840&q=75)