The Full Story of Shazam: The Innovation We Didn't Know We Needed

10 June 2024•

Lucidity Insights just launched a fascinating podcast interviewing the founding CEO, Chris Barton, on the genesis story of Shazam. If you don’t know what Shazam is, you've likely been living under a rock; that, or music is just not your thing.

Shazam was founded on a deceptively simple desire: imagine hearing a song you like, perhaps in a noisy bar, at the mall, on the radio, or at your friend’s wedding, and wanting to find out who the artist is and the name of the song. Before Shazam, we were left with one option, which was to ask those around us if they knew who was playing. Chris imagined an entirely different reality. “What if,” he asked, “you could just hold up your phone in a noisy bar, and discover the name of the song playing in the background within seconds – through a text message?”

With the technology available today, this seems like a simple feel-good app; but the Shazam story is complex and revolutionary because Shazam was established in the year 2000, nearly a quarter century ago. This was during the dot-com bubble, seven years before the first iphone was launched, paving the way for smartphones to become ubiquitous. This was a time when Nokias were the most popular mobile phones, and the extent of their functionality was to send each other text messages through SMS (Short Messenger Services) and play a game called Snake. The truth is, Shazam was created eight years before the world knew what an app was. Shazam was even established a year before the first ipod was released, and three years before the itunes store came into being, where hundreds of thousands of songs were catalogued on a database.

Riding the Mobile Phone Wave

Riding the Mobile Phone Wave

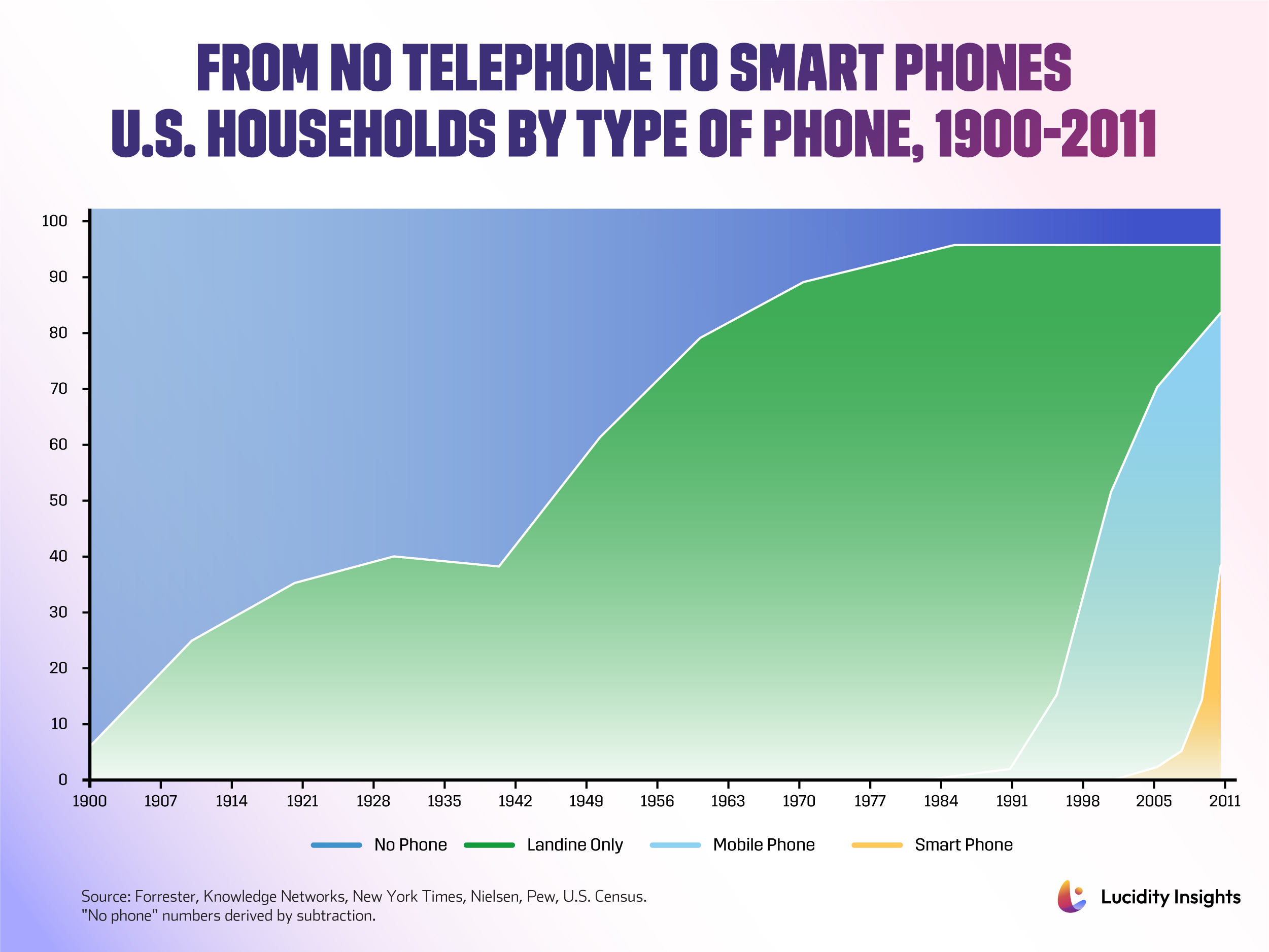

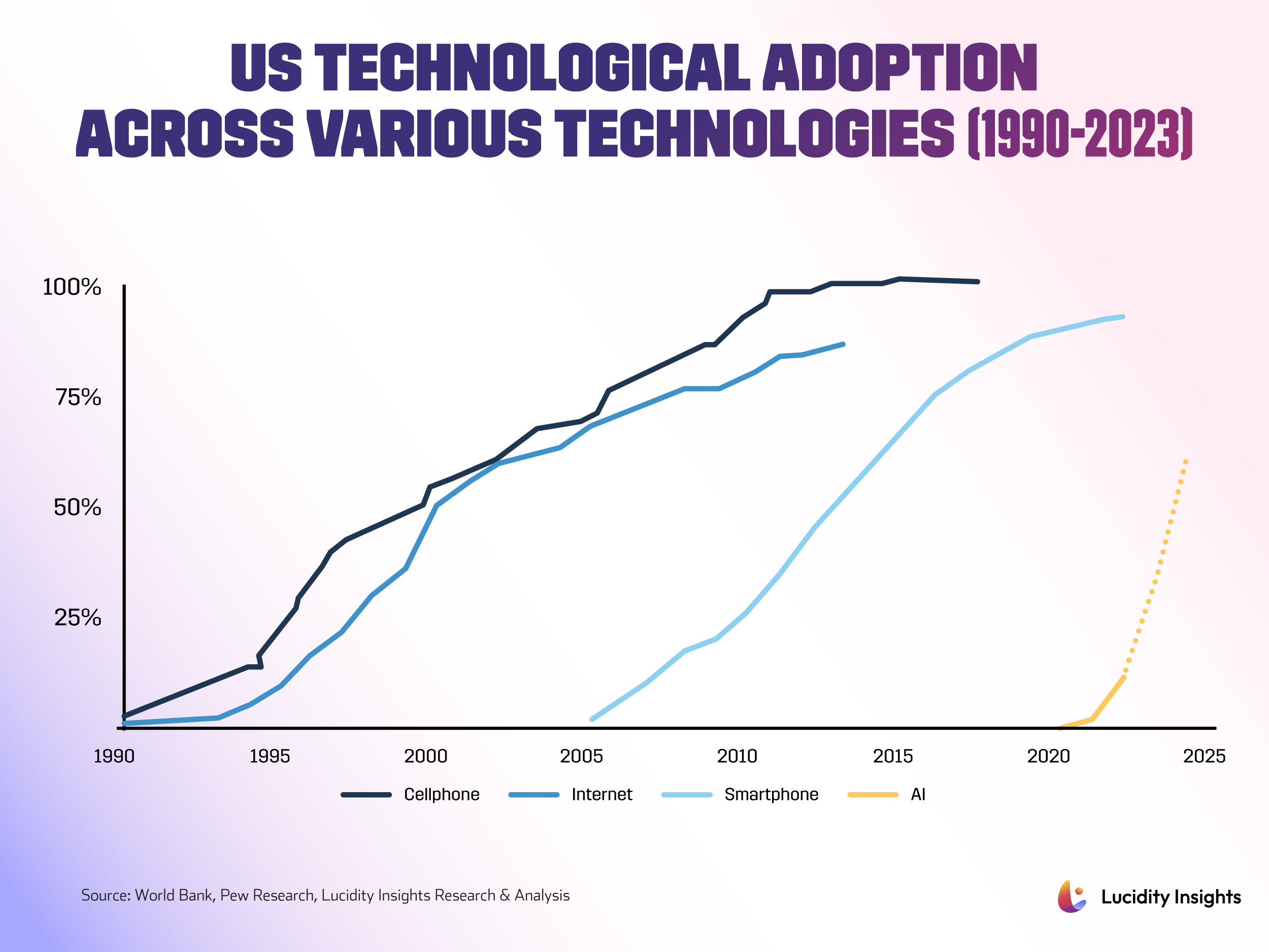

During his MBA at UC Berkeley in the late 90’s, Chris was observing the rapid adoption of mobile phones across the US and the developed world in the 90s. We’re not talking about the adoption of smartphones here, we’re talking about basic, “dumb” cellphones. The rate of adoption around the world was unlike anything we had seen since the adoption of television. We have seen similar archs of technological adoption since then, such as the rapid adoption of the internet in the late 90’s and early 2000’s, and again, the rapid adoption we are now seeing of Artificial Intelligence (AI) through the advent of ChatGPT.

Chris saw an untapped potential that extended beyond calls and texts, laying the foundation for Shazam. So, he embarked on a mission to create a service that could identify music from brief audio clips alongside his friends and future co-founders Dhiraj Mukherjee and Philip Inghelbrecht.

Chris said, “Someone once told me, ‘You invented an app eight years before apps existed,’ and it blew my mind, because I had never thought of it that way. Obviously, I didn't think of it as an app at the time because there were no apps.”

He then explained that at the time of establishing Shazam, he had seen a graph of what percentage of people had mobile phones, and it might have been 40% or 50% of people. He went on to say, “A couple of years after I came up with the idea of Shazam, it was maybe 70% to 90%. Suddenly everyone was getting mobile phones, so I was genuinely fascinated by the opportunity."

The Technology Didn't Exist

The Lucidity Insights Podcast goes on to detail the various challenges of developing the technology to get this idea off of the ground, and to prove a viable business model. The first hurdle was the technical challenge, as they quickly discovered that there was no existing technology they could cobble together to make this dream a reality.

"There was no technology that could do it, and there was also no expert PhD audio signal processing person that said, yeah, I could build that for you. So, at that point, there definitely was concern, I would say, from all my co-founders,” he laughs. "Like, wait... hold on, we're building a company using a technology that we haven't invented and no one knows how to invent?"

That's when they brought on a Stanford PhD student in music-related Digital Signal Processing, Avery Wang, to complete their team who said he was willing to give it a shot, but was himself skeptical about the feasibility. The challenge with the technology available back then was that it could only recognize music from clean signals, typically used by radio stations with small databases of about one hundred thousand songs, and noise cancellation technologies on mobile phones were designed to enhance human voices while suppressing other sounds, including music. After years of development, thanks to Avery and the team’s commitment and perseverance, Shazam finally came to be, but as a music recognition service that is quite different from what we all know and love today. The first iterations of Shazam required users to dial a number through their cellphones, raise their phone up to the music, and then receive a text message with the name of the artist and the song. If it was successfully identified, the user would have to pay a small fee per song identified, which was billed to your mobile phone subscription service.

Was This a Problem Worth Solving?

However, the challenges were not only technical. Convincing investors of Shazam’s potential was equally daunting, as traditional investors back then, especially those in London, where Shazam was established, were skeptical to say the least.

"A typical investor was not the person you imagined using Shazam,” Chris explained, “so convincing them that everyone wants to use their phones to identify songs and that's going to be an entire business in and of itself was very hard to do. One big venture investor watched the demo and he literally said, I don't see why anyone would ever use that. We were in a boardroom at the VC firm, and when he said that, I kind of thought for a moment and said, ‘let's go out this room right now and we're going to go to the desks of all those people [who work for you] and we're going to just ask them if they would use this.’ And it wasn't really an appropriate thing to do, especially in conservative London where he was an ex-Goldman Sachs investment banker. So he was kind of put off by that a little bit. He sort of paused, but then he said, ‘Well, I guess there's quite a large market for Barbie dolls and I would never buy a Barbie doll.’ And I thought that was insightful that he said that. Then the next thing he said was, 'I wish the entrepreneurs I funded had that kind of oomph.' Because it was like, yeah, well, I'm going to take you on.” Chris admitted with a smile, that that investor did not come onboard Shazam’s cap table.

Admittedly, there was also this question of “what problem were you really solving, with Shazam.” It’s a nice to have, at best. In today’s world, there is a real question as to whether or not this innovation would have gotten the backing it needed to become what it is today.

Nonetheless, the team's persistence paid off. Chris spoke into how they primarily cold-called to secure angel investments from individuals in the music and telecom industry who could lend credibility to their venture. These angel investors included the former chairman of EMI Records and the CTO of British Telecom, who strategically boosted their credibility to approach even larger venture capitalists. These cold calling stories alone are so insightful, of how Chris looked up various executives’ phone numbers in the phone book, and gave them an elevator pitch to secure a meeting.

Shazam's Many Business Models

Initially, Shazam generated revenue through a premium SMS model, charging users around 50 pence per song identification.

"We did partnerships with all four major mobile phone companies to launch in the UK because that phone number you dial was a four-digit number, 2580, and to get a four-digit number as your phone number, you have to have a partnership with a mobile phone company because they control these short codes. There's four major mobile operators in the UK: Vodafone, Orange, T-Mobile, and O2, and we needed that [same] number on all four mobile operators. If one of them said, no, you can't have 2580, of course that would be a disaster because now we'd have different phone numbers on different carriers. So, yeah, that was super interesting," Chris recalls.

In a little over a year, Chris and the team had raised roughly about a million dollars in their Angel round as a bridge loan, and then their Series A came in at US $7.5 million.

As the digital landscape evolved, Shazam adapted, forming licensing deals with mobile manufacturers like Samsung and Motorola and partnering with iTunes for digital music sales. In-app advertising later became a significant revenue stream, diversifying Shazam’s income sources. But this was an eight year journey where Chris explained that Shazam was close to shuttering its doors many times.

"When a startup hits hard times, what you normally do is you start cutting costs, and you seek out more funding,” says Chris. “Those were the only two options. So what we did, was we got creative about finding other funding streams.”

Shazam went through many different business models, as they were burning through cash for many years without reaching profitability. Just some of the different ways in which they were able to bring in revenue involved creating a technology for old Samsung phones to identify MP3 songs transferred onto phones, and correctly labeling them; creating a white label native Shazam-type app called ”MotoID” for Motorola phones, in the time before apps; and they did something similar for AT&T. At one point, they even sold their exclusive license to launching Shazam in Japan in the future.

They also built a B2B business that displaced the existing radio recognition companies working to get royalties paid out to artists, because their technology was superior to that was being used in the market. With respect to that service, it seems Chris’ only regret when looking back on how the business was run for the 18 years to the run-up to Shazam getting acquired, was to focus on this revenue generator earlier.

Lucidity Insights’ Podcast host and Chief Content Officer, Erika Welch, asked towards the end of the conversation, “If you were to go back, would you change anything?”

Chris barely paused and said, “the biggest thing I would have changed, is that I would have put the peddle down earlier for these ancillary revenue streams that we went after. Specifically, the best one was the B2B business where we were monitoring radio stations for royalty societies. The lesson I learned was that it did bring in a significant revenue stream that helped us survive. If we had done it earlier, we would have had less crushing dilutive rounds with venture capital firms to stay alive.” He continued, “Sometimes you have to do whatever it takes to survive, even if that means doing things that are not really the priority of the business.”

Saved By the App Store

It wasn’t until the launch of Apple's App Store in 2008, when things shifted. The App Store was a pivotal moment for many emerging technologies, but for Shazam, it was nothing short of life saving. Apple had only selected a handful of apps to feature at launch, so once Shazam had built an app version of what they already had, they were set to receive this unprecedented visibility. At the time, Apple had also selected six apps to highlight the iPhone's capabilities, creating 30-second commercials for each, one of which focused solely on Shazam. “This was huge for us,” Chris said.

The app quickly became a staple for music lovers worldwide through free advertising and word of mouth, for many years achieving 8 million downloads per month without any advertising spend. Today, Shazam has achieved over 2 billion downloads, and there are over 300 million monthly active users today.

The startup story completes when Shazam gets acquired by Apple for a reported US $400 million in 2018, integrating its powerful music recognition capabilities into the Apple ecosystem. This acquisition underscored Shazam’s enduring value and influence in the digital music space, enhancing services like Apple Music and other apps like Spotify and Snapchat, continuing to innovate in music discovery. Today, the app has become a staple for music lovers worldwide, achieving over 2 billion downloads and more than 300 million monthly active users.

%2Fuploads%2Fdubai-digitized-economy-2%2Fcover.jpg&w=3840&q=75)