Cloud Kitchen Business Models

03 June 2022•

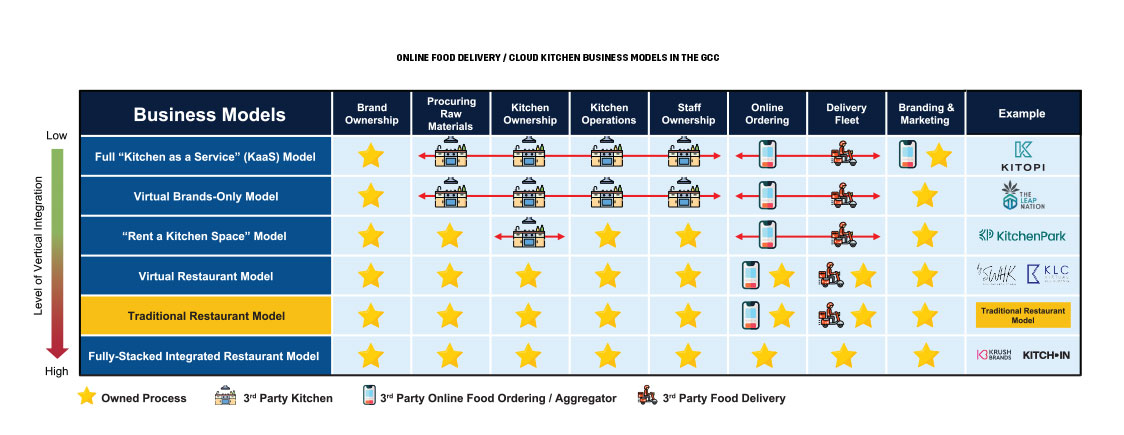

There are many different combinations of how online food delivery companies, restaurants and cloud kitchens can work together meaning that there isn’t a set blueprint or list of business models; and the more businesses we reviewed and more CEOs we spoke to – we realized that the cloud kitchen business models are evolving every day depending on each market’s dynamics. Below, we have mapped out the most typical business models currently found in the GCC region today:

The Kitchen-as-a-Service (KaaS) Model

The Kitchen-as-a-Service (KaaS) B2B model is the business model that KITOPI, our region’s famous foodtech unicorn employs. In this model, a KaaS such as KITOPI essentially becomes a franchisee for different food brands and offers a turn-key solution requiring minimal effort on the F&B brands. The KaaS player learns each recipe, and takes onboard the entire process; everything from sourcing and storing ingredients, preparing and portioning meals at a central kitchen, distributing prepped meal components to different satellite kitchens across the city, hiring and managing cooks to prepare the food at the various satellite kitchens, and ensuring all of their smart-kitchen and ERP technology is up-to-date to maximize efficiency. The KaaS also has a centralized call-centre to trouble-shoot any order or delivery issues. The only job the KaaS subcontracts out, is the online delivery platforms and food delivery – which the KaaS signs up to on behalf of each food brand. In this full-service KaaS model, anywhere between 13-18% royalties are paid by the KaaS to the F&B brand owner. Restaurants and food brands look for KaaS solutions for 2 primary reasons:

They want help to expand their total addressable market by expanding their geographical reach to delivery-only orders outside of the reach of their current restaurants/kitchens

They want to move-out all the delivery orders from their dine-in restaurant kitchens, which aren’t designed for high-volume orders

IkCon and OneKitchen are some of the other KaaS players in the GCC market. Read about KITOPI’s journey to become the region’s first cloud kitchen unicorn on page 16.

The Virtual Brands-Only Model

The Virtual Brands-Only model is exactly what it says on the box: these companies essentially create restaurant brands and menus that are entirely virtual, and only available for delivery, and then outsource everything else. These players design the menus and then launch the various food brands and menus on delivery aggregator platforms, and then contract a full-service KaaS to fill their orders for them. As they increase the number of successful virtual brands they have on the various platforms, they expect to create economies of scale. The benefit of this model is “all brains and limited brawn” – in other words, contract out the heavy lifting, but trust in the menus and data-driven strategic decision making of your creative team. The challenge with this model is the lack of control and visibility along the value chain, and thus it is difficult to pinpoint why a particular F&B brand is failing – is it branding and marketing, the menu itself, or the execution and delivery of the product? But with the right partners, and with enough successful brands, this model has proven to be profitable without the headache of managing extensive operations. Some players in the market employing this business model include The Leap Nation and Cloud Restaurants (read about Cloud Restaurant’s growth in the UAE Country Profile on page 25-27).

The “Rent a Kitchen Space” Model

The Rent-a-Kitchen space model is often confused for the KaaS model. This business model is more of a real-estate play. Players like Kitchen Park, Kitchen Nation and Deliveroo Editions to name just a few, essentially build large “shared” commercial kitchens in strategic locations across a city (housing anywhere from 6 to 50 kitchens in a complex), designed and built with delivery-only restaurants in mind. These players then rent-out these kitchens to various F&B brands, but the brands themselves are responsible for providing their own cooks and procuring their own ingredients, and operating out of the kitchens themselves. The same kitchen can be rented out to multiple restaurants to use, at different times of day – similar to the hot-desk concept in an open office. For example, there may be a breakfast restaurant team that uses a kitchen space in the morning, and a lunch and dinner restaurant for the afternoon and evening. Deliveroo Editions goes one step further by sharing insights off their online food ordering and delivery platform to determine which neighbourhoods various cuisines and restaurant brands are likely to be strong performers, and they provide this opportunity for their F&B brand partners to expand with them into one of their “Rent-a-Kitchen” spaces in the desired neighbourhood.

The Virtual Restaurant Model

The Virtual Restaurant Model most resembles the traditional restaurant model, in everything except it is a restaurant that does not have dine-in as an option (though some virtual restaurants have begun to reverse the trend and open brick-and-mortar restaurants either adjacent to their cloud kitchens or entirely separately). A virtual restaurant owns its’ brand(s), menus, kitchens, kitchen staff, and manages everything from ordering ingredients, preparing meals, cooking, and marketing its products on 3rd party food aggregators and delivery apps. As a customer, you may be ordering online from virtual restaurants regularly, and you may not even know that there is no restaurant to visit and dine-in at. This model seems to provide greatest control to the restaurant across the value chain, and allows them to choose which neighbourhoods to expand their kitchens into. Some of these virtual restaurant players also have their own fleet, and may employ a hybrid model using both their own delivery fleet and the fleet of aggregators. There are single brand virtual restaurants, that do one thing (such as shawarma or pizza) extremely well at scale, and then there are multi-brand virtual restaurants that produce multiple cuisines, restaurant brands and menus in one large virtual kitchen, achieving economies of scale in that way.

Regional examples of single brand Virtual Restaurants include Manou’she Street and Pinza Pizza in the UAE. Multibrand Virtual Restaurants include KLC Virtual Restaurants in Kuwait (you can read their story on page 43), Sweetheart Kitchen in the UAE (you can read their story on page 31), and VResto in Bahrain. What’s most interesting is that we are now seeing some of the successful “delivery-only” virtual brands, such as Pinza Pizza, talking about launching their first brick-and-mortar restaurants – showing us that online restaurants can be a way to provide proof of concept in a relatively quick and cost efficient manner.

The Full-Stack Cloud Kitchen Model

The fully-stacked cloud kitchen is the ultimate self-reliant business model that says “I can do it all”. They own the complete food ordering value chain from ordering, processing, to preparing and delivery. They create and owns their own brands and menus, own and operate their own kitchens with their own staff, own their own online ordering platform(s), and then fulfil the delivery to the end customer with their own delivery fleet. The cloud kitchen has complete control over quality and consistency within this model – but it’s a mammoth task. Krush Brands, based in the UAE, is one of very few examples of a company operating in this way in the market. Krush Brands’ CEO, Ian Ohan, is a strong voice in the region for the full-stack model where F&B chains take the delivery operations and ordering platforms in-house. He’s often quoted as saying that delivery aggregators take too large a chunk out of F&B outlet’s revenues, charging up to 30% plus a delivery charge on top of that in many cases to the customer, making this an unsustainable proposition to restaurants. Kitch-In is another near full-stack player that is redefining the cloud kitchen market by delivering high-end cuisine for delivery and hotel room service. Read more about their story on page 28.

%2Fuploads%2Ffoodtech%2Fcover2.jpg&w=3840&q=75)